LONDON — They established a global business empire that stretched across three continents, and became friends and confidants of Britain’s aristocracy and royal family. But the Sassoon dynasty, which made its millions as traders in opium, cotton, tea and silk, stemmed not from London, Paris or New York — but Baghdad.

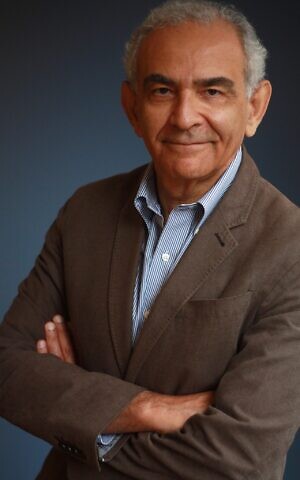

The family’s meteoric rise and equally dramatic fall is told in gripping yet meticulous detail by history professor Joseph Sassoon in his new book “The Sassoons: The Great Global Merchants and the Making of an Empire.” (A Hebrew edition will follow in June.)

It’s not simply a tale of refugees who came to be known as the “Rothschilds of the East,” but also of bitter family disputes, trailblazing female pioneers and a legacy carelessly squandered. “Think ‘Succession’ with yarmulkes,” as the New York Times recently put it.

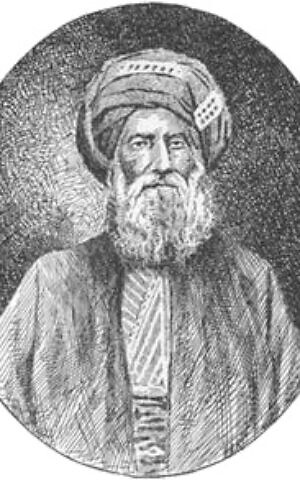

The story begins with David, the dynasty’s founding father, escaping Ottoman Baghdad for Iran in the late 1820s. The son of Sheikh Sassoon ben Saleh, a long-serving former chief treasurer to the city’s pashas, David had been threatened and held hostage by Baghdad’s notoriously greedy and rapacious governor. When the aging Sheikh, once “the most eminent Jew in Baghdad,” joined him soon after, it capped a remarkable fall from grace for the family.

For Joseph Sassoon, the story of their exile from Baghdad — one echoed by his own family fleeing the Iraqi capital during Saddam Hussein’s brutal rule — sparked a connection to his distant relatives. “That sense of looking for security, longevity and stability is so ingrained in anyone who was a refugee,” he tells The Times of Israel.

The Sheikh’s death in 1830 hastened the departure of David and his young family for Bombay where British rule provided safety and the administration adopted a liberal posture stance towards the city’s Jewish community.

Skill, luck and hard work

David had luck: Bombay was the fast-growing commercial jewel in the crown of western India with the cotton and opium trade key to its prosperity. Moreover, he arrived in the city with his father’s carefully cultivated network of contacts among merchant families across the Ottoman Empire and Iran.

But David also had skill. As Sassoon writes, he regarded a good reputation as a “priceless asset” and built long-lasting and enduring bonds of trust and confidence among those with whom the family traded. This lesson, drilled into his two eldest sons, Abdallah and Elias, was the cornerstone upon which the family’s future business success would rest.

David also has a ferocious capacity for hard work. On arriving in Bombay, he swiftly added Hindustani to fluency in Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish and Persian, and spent countless hours getting to know traders and agents at the city’s cotton exchange, while closely monitoring international developments which might affect prices.

Initially trading in textiles, David began a steady but cautious rise. It would be over a decade before he was recognized as one of the major players in the Arab-Jewish trading community. This was another lesson that David was keen to impart to his sons: A fine assessment of risk and avoidance of speculation were to be hallmarks of the business.

David combined his commercial nous with political savvy. From the moment of his arrival in Bombay, sharing its belief in the importance of free trade and enterprise, David aligned himself closely with British imperial interests.

It was a shrewd move. In the First Opium War of 1839-42, Britain quashed China’s effort to stem the flow of the powerful narcotic into the country. David saw the opportunity, dispatching the “energetic and tenacious” 24-year-old Elias to scout the lay of the land and seek out new customers.

The die was cast. Over the following decades, the Sassoons supplanted bigger traders to become the dominant player in the export of opium from India to China.

“The controversial story of opium is woven throughout more than eighty years of the Sassoon dynasty, whose control of the opium trade in India and China by the late nineteenth century was inextricably linked to their wealth and influence,” writes Sassoon.

Elias’s pivotal role illustrates the manner in which David built a truly family business. Having fathered 14 children over 39 years, there was plenty of action to go around. Strict but caring, he schooled his sons in business while encouraging them to travel, appreciate new cultures, and learn independence.

Meanwhile, the profits from opium, which became the world’s most valuable traded commodity, propelled the Sassoon business forward, particularly in the three decades after 1860. Local business branches, overseen by David’s sons and named “House of Bombay” or “House of Shanghai,” were established. As one competitor put it: “Silver and gold, silks, gums and spices, opium and cotton, wool and wheat — whatever moves over sea or land feels the hand or bears the mark of Sassoon & Co.”

Quality products, agility thanks to a diversity of both suppliers and locations to trade, and that reputation for straight dealing — all underpinned the business’ success. So, too, did David’s unquestioned authority and a shared sense of mission within the family.

Business acumen was combined with epic levels of philanthropic giving: one-quarter percent of each trade, whether profitable or not, was recorded as a charitable surcharge, or tzedakah, in branch ledgers. In Bombay, David established a school for boys, one for girls, and a third for underprivileged juveniles. Later, hospitals, libraries and the renowned Sassoon Mechanics’ Institute would follow.

Eastern rise, western fall

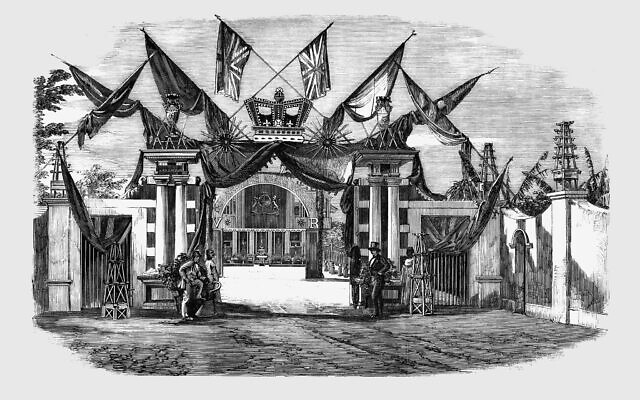

David’s commercial success, loyalty (in the Rebellion of 1857 David offered the British “the services of the whole Hebrew community” of Bombay), and philanthropy did not go unnoticed. In 1853, he was granted British citizenship in recognition of his services to the Empire (ironically, his English was poor and he signed his oath of allegiance to Queen Victoria in Hebrew). Further honors followed and in 1859 his home, San Souci, in one of Bombay’s wealthiest neighborhoods, played host to 500 guests celebrating Britain’s decision to assert a more direct form of control over its prized imperial possession.

Like many empires held together by the glue of a revered and dominant figure, David’s death at his home in Pune at the age of 71 in 1864 proved fateful, if not fatal. The succession had never been discussed; instead, his will anointed Abdallah as his successor, enjoining his other children to “respect and obey my said eldest son.” Elias, who had contributed so much heading the business in China, received just one brief mention.

The healthy element of competition between the company’s various houses — and brothers — which David had hard-wired into the business soon began to curdle into feuding, finger-pointing and resentment once he was no longer present to keep the lid on. Within three years of the founder’s death, the business split in two: Abdallah continued at the helm of David Sassoon & Co, while Elias ran E.D. Sassoon & Co.

Although family ties remained, in business no quarter was given. Abdallah complained bitterly about his brother’s successes, while, even after his early death at the age of 60 in 1880, Elias’s dictum — “Wherever David Sassoon & Co are, we will be; whatever they trade, we can trade” — continued to guide the firm.

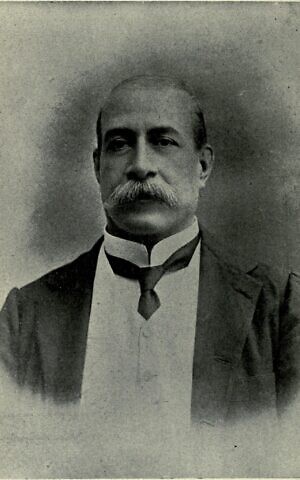

Abdallah’s griping was ungenerous. Under his leadership, the business experienced what Sassoon terms its “golden age.” Thanks to David’s decision to invest in property, insurance and banking, the company rode the downturn in the cotton market and financial crisis which rocked India in the mid-1860s and emerged to join the top tier of global traders. Abdallah, bringing what Sassoon calls a “blend of risk and innovation,” pushed the business to new heights of success. Opium, cotton and textiles still contributed to its healthy balance sheets, but new investments — in an American railway company syndicate, Hungary’s national debt, and banks and property — continued apace.

In other regards, Abdallah continued David’s approach of remaining close to the British. While he was something of a fixture on the Bombay social scene, a member of the city’s legislative council and an adviser to the local governor on educational and building projects, Abdallah began to shift his attention to the west. Having been knighted in 1872 — henceforth, he’d be known as Sir Albert — the British hung more baubles upon him: the following year, Abdallah became the first Jew to receive the Freedom of the City of London. In 1874, Albert moved permanently to London, the imperial capital and the world’s most important commercial city.

The Sassoon trail to Britain had already been blazed nearly two decades earlier by another of David’s sons, Sassoon David Sassoon. The “pioneer of the House of Sassoon in England,” Sassoon David led the business’ expansion in the UK and was soon joined by his brother, Reuben. He spearheaded the family’s break into the upper heights of London’s financial world, while the purchase of a sprawling estate at Ashley Park in the capital’s well-heeled home counties, writes Sassoon, became “the most prominent symbol of both the family’s wealth and their changing aspirations for years to come.”

Unsurprisingly, on his arrival in London, Albert was quickly admitted to the higher echelons of British society. He certainly proved his worth. When the Shah of Iran visited London in the late 1880s, for instance, Albert hired the Empire Theatre for a night of “glittering entertainment.” The move delighted not only the royal visitor and his host, the Prince of Wales (the future King, Edward VII), but also the British government, which viewed Persia as strategically important to the Empire. Shortly afterward in 1890, Queen Victoria rewarded Albert with a further title, a baronetcy.

Albert was not alone in enjoying warm relations with the aristocracy and royalty, both in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. In 1873, his half-brother, Arthur, married Eugenie Louise Perugia, of an old Italian Jewish family. “Mrs. Arthur,” as she was universally known, became a fixture on the London social scene, and regularly featured in Queen Victoria’s diaries. The Sassoons soon also became related to the Rothschilds by marriage with Albert’s son, Edward, marrying Aline, the daughter of Baron Gustave de Rothschild of Paris, in 1887. Edward was later elected to parliament to represent the Kent constituency of Hythe, which has previously returned Meyer de Rothschild as its MP.

It was Albert’s brothers, Reuben and Arthur, who were personally closest to the royal family. They shared with the Prince of Wales, Queen Victoria’s eldest son, a love of horse racing, shooting and hunting. Edward and his “Marlborough House set” of fashionable friends enjoyed the “gay parties” thrown by Arthur and his wife at their estate in the Scottish Highlands. Reuben became known as the Prince’s “unofficial bookie” and “administrator of funds for his past times.”

Albert, however, never allowed his new life in Britain to distract him from his responsibilities to the business, even as his Bombay-based half-brother, Suleiman, largely minded the store in the East. The Sassoons’ fortunes continued to prosper even during the economic downturn which rippled out from London across the Empire during the closing years of the 19th century.

But, as Sassoon writes, Albert’s death in 1896 marked “the beginning of the end” for the company. The storm clouds were already on the horizon. Despite the fact that, from the 1890s, profits from opium had begun to fall, the Sassoons failed to sufficiently diversify. Moreover, while they managed to fend off political and religious pressure in Britain to ban this “evil trade,” the writing was on the wall as the new century commenced. In 1907, for instance, Britain agreed with India and China that, within a decade, opium exports and cultivation would be barred. Six years later, Britain further tightened the screw. Both Sassoon companies, however, continued trading the drug, attempting to squeeze every last penny from the now-discredited trade.

Sassoon cautions against solely viewing the family’s participation in the opium trade through a contemporary moral lens. He points out that the drug was legal and freely available as a source of pain relief in pharmacies, while its price was quoted in the financial press. Nonetheless, he believes, the family should have “dropped out” of the dying trade long before it did both for business reasons and because to have kept “hanging around until the last box” was sold was “squalid.”

Progress squandered

Nothing was preordained about this sorry outcome. When Suleiman, who had largely been running business operations outside of England, died in 1894, his remarkable wife Farha took the reins. Outgoing and assertive, she had already been accompanying her husband into the office in the years prior to his death and saw no reason why she shouldn’t now slip into his shoes. Although reluctant about having a woman in charge, Albert knew the company lacked an alternative boss who matched her skills. Aged only 38, the mother of three children became the first woman to run a global business.

Albert’s confidence in her abilities was well-placed. Despite the multiple challenges faced by the company, not least the threat to the money-spinning opium trade, Farha quickly earned the confidence of her employees and drew international attention. A detail person — attributed to her studies of the complexities of the Bible and Talmud — she set about modernizing the company’s methods and practices, imposing order on its sloppy borrowing and lending, and smoothing the counterproductive competition with E.D. Sassoon.

“She was obviously a bulldozer in the sense that you can’t really stop her,” jokes an admiring Sassoon.

But Farha’s extraordinary reign was to be short-lived. With Albert’s death, she lost a crucial protector and, despite being the most senior and experienced partner, was brought down in an internal coup engineered by disgruntled family members in 1901.

“She was running the whole gamut of work from beginning to end and that’s what annoyed the men, they just couldn’t accept it,” says Sassoon.

Fahra was down but not out. Settling in London, the matriarch of the family threw herself into her passions — women’s rights, Judaism, globetrotting, and her children — with gusto. On her death in 1936, Flora (as she had been known since moving to the UK) finally received the recognition her brothers-in-law had denied her. She had, noted one magazine, managed the company “entirely alone … for six years with great success.”

Flora wasn’t the only female pioneer in the Sassoon family. In 1893, Sassoon David’s daughter, Rachel, became editor of her father-in-law’s weekly Sunday newspaper, The Observer. At the age of just 35, she was the first woman to edit a national newspaper. Two years later, Rachel acquired and assumed the editorship of The Observer’s principal rival, The Sunday Times. At The Observer, Rachel broke the story that Charles Esterhazy had confessed to her that he had forged the documents which wrongly convicted Alfred Dreyfus for treason. The interview was accompanied by a blistering leader column in which Rachel accused the French army of antisemitism and demanded a retrial.

Flora’s ousting from the company proved a hinge moment and, within five years of her departure, it was being described by one bank as “a more or less declining firm.”

Extraordinarily, Sassoon says, Flora had been cast aside — but none of the plotters actually wanted to take charge.

“My blood was boiling when I was writing about it,” he says. “Normally in a putsch someone desperately wants the job, but there was no one who wanted the job.”

Waning interest

For a short period, Edward, the MP for Hythe, became chair. When he died in 1912, his son, Philip, was both elected to his former seat and would eventually assume the chairmanship of the company. But neither man was interested in, nor actively involved themselves in, the now listless family business. The exceedingly wealthy Philip — who was close to the prime minister, David Lloyd George, and would eventually serve in government for over a decade as aviation minister — was more interested in politics and the arts, to which he was a generous benefactor.

Philip was not simply uninterested in the business. He also had little affection for his Baghdadi and Jewish roots.

“Once you lose that identity you lose a very strong component of it: of the reason for success going back to being a refugee and this drive to work hard and to prove something,” Sassoon says.

After his early death at the age of 50 in 1939, the family’s involvement in the firm effectively came to an end. It soldiered on in different forms until the 1980s when the British government declared two of its former partners “totally unfit” to be directors.

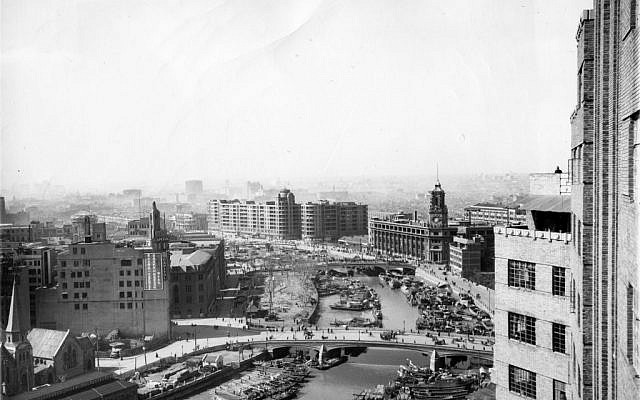

Ironically, the schismatic E.D. Sassoon & Co put up much more of a fight under the leadership of its founder’s grandson, Victor, who became chairman of the company in 1924 upon the death of his father. Fiercely anti-communist and unsympathetic to Indian nationalism, Victor came to see China as a better bet for his commercial interests and transferred much of his wealth — an estimated $25 million (or $500 million in today’s money) — to Shanghai in the late 1920s. He plunged vast amounts into lucrative property investments, including constructing the city’s first 11-story building, Cathay House. By the mid-1930s, Victor was hailed by Fortune magazine as “Shanghai’s No. 1 realtor” with his properties estimated to be worth between $1.2-$1.5 billion in today’s money.

But the Japanese invasion of China, which reached Shanghai in 1937, and the Communist takeover just over a decade later, knocked the financial stuffing out of the company. Having badly gambled on China over India, Victor made a further major error of judgment by then pulling out of Hong Kong — a good long-term bet — after the war. Instead, the luxury-loving Victor opted to live out his remaining years in the tax haven of the Bahamas, pursuing his passion for horse racing, travel and amateur photography. Without the involvement of a Sassoon, his company soldiered on for another decade until, with only diminishing profits to its name, it was sold to a merchant bank in the early 1970s. For all his accomplishments in Shanghai, Victor had ultimately proved, in the words of one of his father’s business associates, “casual about the empire he inherited.”

Victor was hardly the only member of the family to whom this label could be attached. The complacency, lack of innovation, and failure to plan for the long-term which washed over David Sassoon & Co. — exemplified by its failure to shake its reliance on the opium trade and poor tax planning — was wrapped up with the later generations’ attitude towards the business. As they joined the ranks of Britain’s upper classes they imbibed its preference for leisure and snobbish distaste for “grubby” money-making. This attitude was well-captured by the Countess of Warwick’s explanation for why some of the young aristocrats with whom the Sassoons fell in somewhat resented them. “They had brains and understood finance,” she said. “As a class we did not like brains. As for money, our only understanding of it lay in the spending, not the making of it.”

Thus, as Sassoon writes, the family gradually “abandoned the work ethic laid down by the founder and diligently followed by Albert and Suleiman.”

“Most of the family,” he adds, “was keen to extract capital from the company to fund their lifestyles and avoid being actively involved in business.”

Joining the ranks of the British upper crust did not inevitably torpedo the Sassoons’ businesses; other Jewish families managed to do so with their commercial interests unscathed. But, for the Sassoons, the higher they climbed the social ladder in the country to which their business interests had always been so closely aligned, the more they distanced themselves from the very qualities which had made the family — for one glorious but short moment — global trading barons.

Content Source and Photos minus exact title: By ROBERT PHILPOT; https://www.timesofisrael.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-opium-fueled-sassoon-dynasty-the-rothschilds-of-the-east/

![]()

- Islamization of America: Zohran Mandani’s Nefarious Pet Project - February 11, 2026

- A Western DEI Experiment India Did not Need: From Viksit Bharat to WokeShit Bharat - January 27, 2026

- Cinema as Reckoning: Supernatural Justice for Hindu Pandits in Baramulla - January 6, 2026