The Miyawaki method is an innovative approach to planting forests garnering global attention as a quick way to “greenify” cities. Its imitation of natural processes to create diverse woodland ecosystems makes it possible to reestablish native stands in a span of just a few decades. A student of plant ecologist Miyawaki Akira, the developer of the technique, explains the approach and talks about the importance of fostering urban forests.

Forests play a huge role in sequestering carbon dioxide, making them essential to offsetting emissions as the world races to achieve carbon neutrality. Japan has seen its forested land increase, the result of once closely managed areas like satoyama and secondary forests in rural farming communities being left to grow wild as populations in the countryside shrink. Green spaces in cities, on the other hand, continue to dwindle as urban areas swell. Below, I look at the benefits of urban forests, and describe how cities can regrow stands of native trees using the Miyawaki method.

A Data-Driven Approach to Urban Forests

The Miyawaki method of afforestation is the invention of renowned plant ecologist Miyawaki Akira. Professor emeritus at Yokohama National University and former president of the International Association of Ecology, Miyawaki remained a staunch advocate of restoring indigenous forests to urban areas until his death in July 2021 at the age of 93. He developed his pioneering method based on an extensive body of research data on plants in Japan and elsewhere, which he compiled into the 10-volume Nihon shokusei shi (Vegetation of Japan).

Miyawaki first utilized his method to plant a forest at the Nippon Steel Corporation’s plant in Ōita Prefecture in 1972. This approach would later blossom into the creation of what he from the beginning called furusato no mori, “hometown forests,” at locations other than factories throughout Japan. Following this inaugural project, he published an influential work in 1974 outlining his approach that focused on restoring native forests at Japanese educational institutions. Then in 1976, he put these ideas to work establishing another forest, this one on the campus of Yokohama National University in Kanagawa Prefecture.

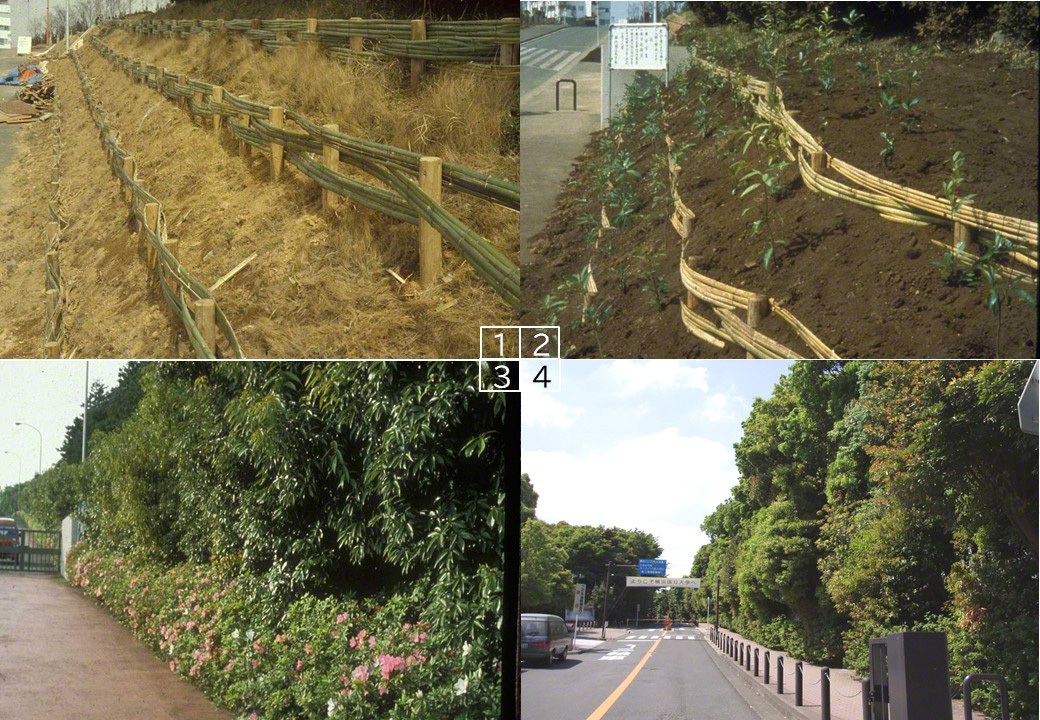

(1) The site for the Miyawaki forest at Yokohama National University was a 2–3 meter embankment covered in invasive species of grass. (2) Topsoil was added and varieties of shii (Japanese chinquapin), tabu (Japanese bay tree), and kashi (Japanese oak) were planted. (3) Three years after planting, the trees had grown to 3 meters. (4) A decade after planting, the trees had reached 10 meters in height. (Courtesy of Miyawaki Akira)

Since its inception, Miyawaki’s technique has drawn the attention of experts in Japan and from overseas who have studied the method and reported their findings in books, journals, and other publications, creating a significant body of literature. These include a recently released report by the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies Japanese Center for International Studies in Ecology, where Miyawaki served for many years as director.

A half century on, Miyawaki’s method has been used to restore forests around the globe. To date, some 900 projects in Japan have utilized the technique, including those to reestablish protective coastal forests devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake’s tsunami in 2011, as well as more than 300 afforestation efforts in such far-flung places as Southeast Asia, the Amazon, Chile, and China.

A Quick Path to Restoring Native Forests

The Miyawaki method is pioneering in its reliance on a large number of native species and the close proximity in which vegetation is planted. It mimics the natural distribution of plant varieties in native forests, enabling the biotopes to grow and mature more quickly than with traditional afforestation methods. The following are some of the defining characteristics of the technique.

1. Selecting Native Species

Core to the technique is the process of selecting native species that are best suited to the local ecosystem. In most cases, cities hoping to establish urban forests have to look elsewhere to identify plant species native to the area, including by surveying large old-growth trees in areas like the sacred forests (chinju no mori) of Shintō shrines. Another resource is overgrown satoyama and secondary forests in rural areas, which are seeing a return of broad-leaf evergreen varieties like native oak and chinquapin. However, differences in conditions like climate, terrain, and soil at survey areas and planting sites must be carefully considered when choosing tree varieties, and a diverse range of indigenous plant species—as many as 40—occupying different forest layers is required.

2. Collecting Seeds

Another important aspect of the Miyawaki method is its focus on keeping things local. Rather than ordering saplings from far off nurseries, native plants should be grown from seeds collected from adult specimens nearby the site. Old-growth trees of species like bay, chinquapin, and oak are abundant in rural areas and are excellent sources of seeds. Teaming up with local nurseries is another good option. However, there must be strict guidelines to prevent the accidental introduction of closely related species at a site in order to ensure the genetic integrity of a forest.

3. Hand-Grown Plants

Once seeds are collected, they are placed in trays to germinate. The sprouts are then transferred to plastic planting pots and are cared for until they have reached a size that they can be transplanted. When planting a Miyawaki forest, selecting saplings with robust root balls is crucial, as these have a better chance of surviving and quickly growing into adult trees.

There are two main options available for preparing the needed number of saplings. Planners can work with local nurseries to acquire or grow saplings, or coordinate with groups that cultivate diverse types of trees as part of environmental awareness efforts. Individuals can also pitch in to produce a small number of plants on their own.

(1) Sprouted seeds are transplanted into plastic planting pots. (2) Saplings grow at a nursery. (3) A sapling of a Japanese bay tree with a fully developed root ball. (4) Net bags containing saplings await transfer to the planting site. (© Suzuki Shin’ichi)

4. Boosting Environmental Awareness

Planting takes place on reprepared embankments that have been fortified with materials that enrich and protect the soil and help with water retention. The planting area is divided into one-square-meter plots, on which three or more different species of plants, typically three-year-old saplings standing around 50 centimeters tall, are planted. The planting process is straightforward, consists mainly of digging holes with hand-held planting trowels and placing the sapling inside, and can easily be coordinated as a group activity. Large projects can be conducted as part of local efforts to raise environmental awareness, with planting volunteers being recruited from surrounding communities. At one such “planting festival” to restore coastal woods destroyed by the tsunami in Iwanuma, Miyagi Prefecture, 10,000 volunteers came together and planted 100,000 saplings in a single day on a sprawling 50-by-100-meter site.

Planting events help raise community awareness of environmental issues and are especially suited to children, helping spur interest in similar projects. They also provide opportunities for like-minded people to meet, and there are many instances of participants going on to form dedicated groups that actively take part in planting events.

(1) A prepared embankment stands ready for planting at a large-scale planting event. (2) Potted saplings are lined up for transplanting. (3) Saplings of different species are planted together in small, square plots. (4) A layer of rice straw mulch is laid out and secured against the wind. (© Suzuki Shin’ichi)

5. Tending Young Forests

Once planted, the closely spaced saplings compete with their neighbors for available resources, spurring plants to grow quickly. A newly planted site needs to be tended for the first few years, including regular watering and the addition of a layer of rice straw mulch to control weeds. After three to five years, though, Miyawaki forests are self-sustaining once trees develop to a size blocking sunlight from reaching the ground, making further human intervention like weed prevention unnecessary.

Miyawaki forests grow rapidly, around a meter a year in height. In as little as a decade, an area with no vegetation can be transformed into a native forest with trees standing 10 meters tall. And in another decade, it will be fully developed, with indigenous vegetation occupying the different layers, including a canopy soaring 20 meters or more in the sky.

The Gold Standard of Urban Forests

Urban concentration is responsible for dwindling wooded areas in major cities. This trend needs to be reversed, though, as such green spaces play a number of vital roles beyond just beautifying the urban environment. Trees shade roads and buildings, helping to fend off the heat-island effect. Stands of trees also protect against natural calamities, an important characteristic in disaster-prone Japan. For instance, after major earthquakes, urban forest act as fire breaks, checking the spread of devastating conflagrations that follow powerful temblors, along with other disaster mitigation functions.

Cities wanting to “greenify” can look to Tokyo’s Meiji Shrine forest for inspiration. Established in 1920, the man-made forest has flourished over the last century without intervention by humans. Considered the gold standard of urban reforestation, experts have rigorously studied the workings of the biotope and its effect on the surrounding urban environment.

There is no need—nor is it be practical—for cities to create something as grand as the Meiji Shrine forest, though. Instead, municipal authorities should utilize the Miyawaki method to strategically plant many smaller stands. Undertakings of this kind would make cities healthier for residents and increase biodiversity while also bolstering disaster readiness, decreasing noise pollution, and mitigating climate change.

The man-made forest at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Higashi-Ōgishima Thermal Power Station in Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture. Starting in the 1980s, saplings were planted at the site, first just one plant per square meter, as shown at left. Later plantings increased this to three. More than 10 years later, the trees, which have yet to reach full height, have formed a dense forest. (Courtesy of Miyawaki Akira)

Source: nippon.com; (Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Planted in 1972, the Miyawaki forest at Nippon Steel Corporation’s Ōita steelworks is now, a half-century later, a self-sustained biotope. Photographed in 2021; © Green Elm.)

![]()

- Due Process Denied: The Buck Stops with Modi - February 19, 2026

- Islamization of America: Zohran Mandani’s Nefarious Pet Project - February 11, 2026

- A Western DEI Experiment India Did not Need: From Viksit Bharat to WokeShit Bharat - January 27, 2026